This lecture is going to develop asymptotic notation mathematically and how to solve recurrences.

Asymptotic notation

${ O }$ notation

${ f(n) = O (g(n)) }$ means there are consts ${ c>0, n_0 > 0 }$ such that (assume ${ f(n) }$ is non-negtive)

Ex. ${ 2 n^2 = O(n^3) }$

Notice, ${ f(n) = O (g(n)) }$ doesn’t means ${ g(n) = O(f(n)) }$. The ${ O }$ notation is not asymmetric. Actually, we can treat ${ O(g(n)) }$ as a set of funtions.

So, when we talk about ${ f(n) = O(g(n)) }$, actually, it means ${ f(n) \in O(g(n)) }$

Macro convention

A set in a formula represents an anonymous funtion in that set.

Ex. ${ f(n) = n^3 + O(n^2) }$

That means there is a funtion ${ h(n) \in O(n^2) }$ such that ${ f(n)=n^3+ h(n) }$

Ex. ${ n^2+O(n) = O(n^2) }$

That means for any ${ f(n)\in O(n) }$, there is an ${ h(n)\in O(n^2) }$, such that ${ n^2+f(n)=h(n) }$.

${ \Omega }$ notation

Define: ${ \Omega(g(n)) =\left\{ f(n): \text{ there are consts } c>0, n_0 >0 \text{ such that } 0 \leq g(n) \leq cf(n), \text{ for all } n \geq n_0 \right\} }$

Ex. ${ \sqrt n = \Omega(\lg n) }$

${ \Theta }$ notation

Define: ${ \Theta (g(n)) = O(g(n)) \cap \Omega (g(n)) }$

${ o }$ and ${ \omega }$ notation

Define: ${ o(g(n)) = \left\{ f(n): \text{ for any const } c>0, \text{ there exists const } n_0 >0 \text{ such that } 0 \leq f(n) \leq cg(n), \text{ for all } n \geq n_0 \right\} }$

Define: ${ \omega(g(n)) = \left\{ f(n): \text{ for any const } c>0, \text{ there exists const } n_0 >0 \text{ such that } 0 \leq g(n) \leq cf(n), \text{ for all } n \geq n_0 \right\} }$

Ex. ${ 2n^2 = o(n^3) }$,

Ex. ${ \frac{1}{2}n^2 = \Theta(n^2) }$ but ${ \neq o(n^2) }$

Solving recurrences

Substitution method

-

Guess the form of the solution

-

Verify by induction

-

Solve for consts

Ex. Solve the following recurrences

Ans:

-

Guess: ${ T(n) = O(n^3) }$

-

Induction: Assume ${ k<n }$ is correct, that is

- Now, let’s check

So, ${ T(n) \leq cn^3 - \left(\frac{c}{2}n^3-n\right) }$, which at most ${ cn^3 }$ when ${ \frac{c}{2}n^3-n \geq 0}$. That is we can find ${ c }$ and ${n_0 }$, such that ${ T(n) \in O(n^3) }$, e.g. ${ c\geq1, n_0=1 }$

The base case is trivial, it’s easy to find some sufficient large ${ c }$, such that

Actually, the above proof is from the class video, I thought it's not rigour mathematically. Therefore I will show another proof in the following.

Let ${ C=\max \left\{\frac{1}{2},\Theta(1)\right\} }$ when ${ n=1 }$, ${ T(n)=\Theta(1)\cdot n^3\leq Cn^3 }$ when ${ n \leq k-1 }$, assume for ${ T(n)\leq Cn^3 }$ consider ${ n = k }$, that isWe just prove a strong conclusion, that is, for all ${ n\in \mathbb{N}^+ }$, we can get ${ T(n)\leq Cn^3 }$. Actually, we just need to prove that when ${ n\geq n_0 }$, we can find constant ${ C }$ to satisfy ${ T(n)\leq Cn^3 }$. Actually, we can prove there exists ${ n_0 >0 }$, such that ${ T(n)\leq 2n^3}$ when ${n>n_0 }$, that is ${ C=2 }$ (in fact ${ C>2 }$ is also OK). This is another strong conclusion, but for ${ C }$.

Let ${ n_0 = \max\{1,\Theta(1)\} }$. First, we prove ${ n=n_0 }$ is rightTo sum up, in fact the prove from video is not very rigor, becasue the const ${ C }$ is not the same one in the cases of ${ n>1 }$ and ${n=1 }$. For the following proof I gived, the clue of my proof is fixing ${ C }$ or ${ n_0 }$ to prove ${ T(n) = O(n^3) }$.

In the following, we will prove that ${ T(n) = O(n^2) }$,

-

Guess: ${ T(n) = O(n^2) }$

-

Induction: Assume ${ k<n }$ is correct, that is

Why we choose the assumption ${ T(k) \leq c_1 \cdot k^2 -c_2 \cdot k }$?

Out of intuition, maybe we will figure out ${ T(k) \leq c \cdot k^2 }$ at first, but we will find that ${T(n) \leq cn^2 + n}$, so we can not go on our induction. Therefore, this form may give us some inspiration, to use a stronger assumption to do induction.- Now, let’s check

So, here we can let ${ c_2 > 1 }$ to guarantee ${ (c_2 -1)\cdot n > 0 }$. So we can finish our induction. Besides, for the base case

Therefore, we need ${ c_2 >1 }$ and ${ c_1 > \Theta(1) + c_2 }$.

Recursion-tree method

Recursion-tree usually works and can give us an intuition to know the answer, but it’s slightly non-rigorous!

Technically, we should use resursion-tree method to find the answer and use substitution method to prove it rigorously.

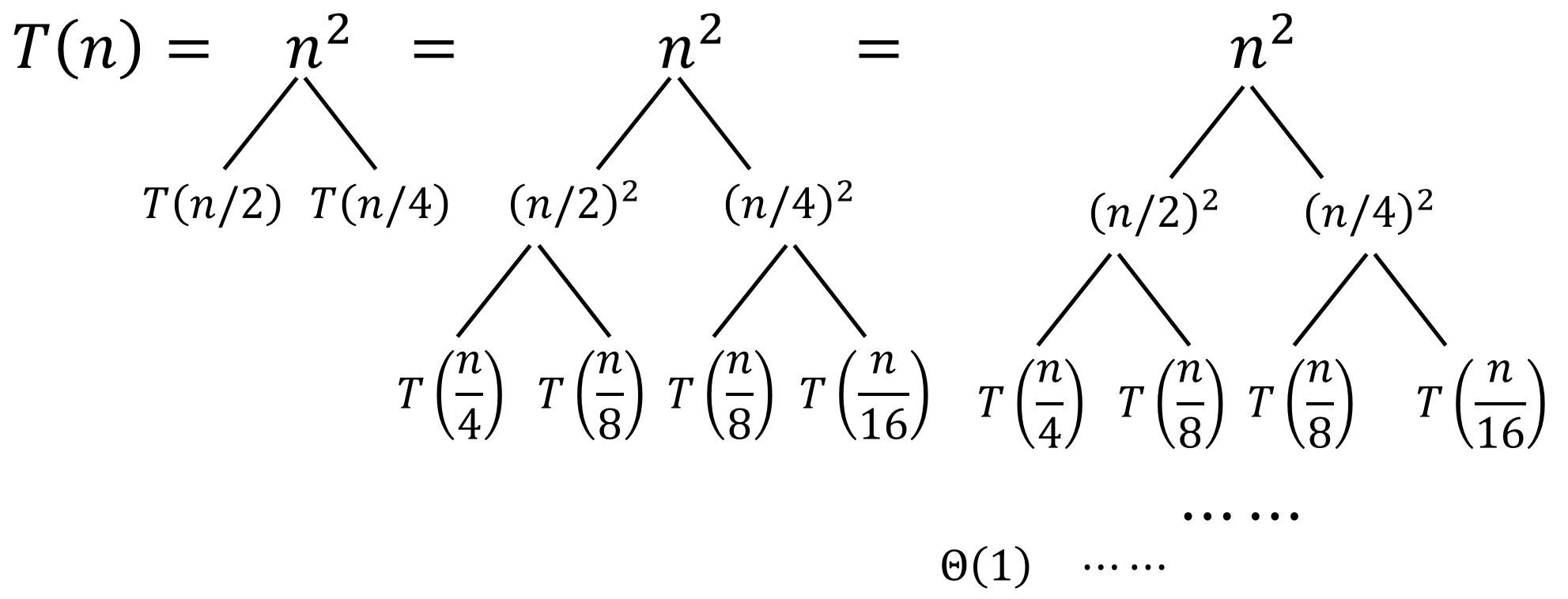

Ex. ${ T(n)=T(n/4)+T(n/2)+n^2 }$

We can build a “Recursion Tree” as follow

First, we can know that the number of leaves is less than ${ n }$.

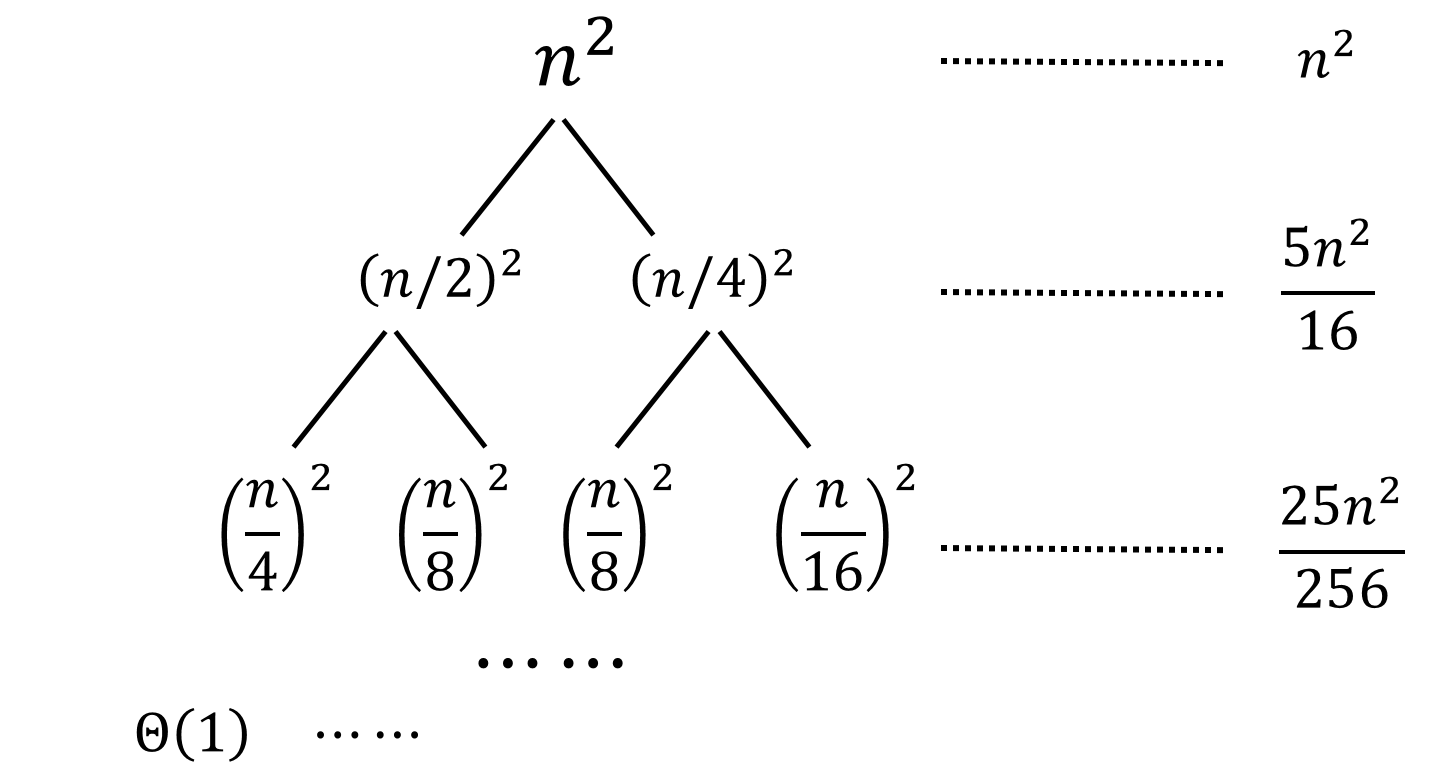

If we divide ${ T(n) }$ to four ${ T(n/4) }$ or two ${ T(n/2) }$, the number of leaves will be ${ n }$. But, here ${ n/4 + n/2 = 3n/4 <n }$, so the number of leaves must less than ${ n }$.Then, we will calculate the sum of tree level by level. Through observation, we find that the sums of each level construct a geometric series (see the following figure).

Therefore, we can calculate the upper bound of ${ T(n) }$ (the height of tree is a finite number, but we treat it as a infinite geometric series.)

In the meantime, it’s easy to get ${ T(n)>n^2 }$, so ${ T(n) = o(n^2) }$. Therefore ${ T(n) = \Theta(n^2) }$.

Master method

We can treat the Master method as an application of the recursion-tree method. In detail, we apply resursion-tree method to a particular family (as below) of recurrences to get Master theorem.

Note! Asymptotically positive: there exists some ${ n_0 }$, when ${ n>n_0, f(n) >0 }$.

Compare ${ f(n) }$ with ${ n^{\log_b a} }$

Case #1: ${ f(n) = O\left(n^{\log_b a - \varepsilon}\right) }$ for some ${ \varepsilon >0 }$.

${\Rightarrow}$ ${ T(n) = \Theta\left(n^{\log_b a}\right) }$

Case #2: ${ f(n) = \Theta\left(n^{\log_b a}(\lg n)^k\right) }$ for some ${ k\geq 0 }$

${\Rightarrow}$ ${ T(n) = \Theta\left(n^{\log_b a}(\lg n)^{k+1}\right) }$

Case #3: ${ f(n)=\Omega(n^{\log_b a+\varepsilon}) }$, for some ${ \varepsilon >0 }$. And ${ af(n/b)\leq (1-\varepsilon’)\cdot f(n) }$ for some ${ \varepsilon’ >0 }$

${\Rightarrow}$ ${ T(n) = \Theta\left(f(n)\right) }$

Ex. ${ T(n)=4T(n/2)+n }$

Ans: Here ${ a=4,b=2,f(n)=n }$, compare ${ n^{\log_2 4} = n^2 }$ with ${ f(n)=n }$. ${ f(n)=O(n^{2-\varepsilon}) }$ here we can take ${ \varepsilon=1 }$. So, we are in Case #1, that means ${ T(n)=\Theta(n^{\log_2 4})= \Theta(n^2) }$

Ex. ${ T(n)=4T(n/2)+n^2 }$

Ans: Here we are in Case #2, because we can choose ${ k=0 }$, so ${ f(n)=n=\Theta\left(n^2(\lg n)^0\right) }$. Therefore, ${ T(n)=\Theta(n^2 \lg n) }$

Ex. ${ T(n)=4T(n/2)+n^3 }$

Ans: First, let’s check

Here we take ${ \varepsilon’=\frac{1}{2} }$. And ${ f(n)=n^3 = \Omega(n^{2+\varepsilon}) }$, here we can let ${ \varepsilon = 1 }$. So we are in Case #3, then we can get ${ T(n)=\Theta(f(n))=\Theta(n^3) }$

Ex. ${ T(n)=4T(n/2)+n^2/\lg n }$. Warning: here Master method doesn’t apply to it.

Proof of Master Theorem

At first, we can draw the recursion tree of recurrence ${ T(n)=aT(n/b)+f(n) }$. Then, we can calculate the height of the tree. In ${ i^{th} }$ level, the cost of each note is ${ f(n/b^i) }$, and the cost of each leaf is ${ T(1)=\Theta(1) }$, so the height of tree ${ h }$ is ${ \log_b n }$. (Because ${ n / b^h = 1}$). Besides, in each level, each notes will have ${ a }$ children, so the number of leaves is ${ a^{\log_b n} = a^{\frac{\log_a n}{\log_a b}}=\left(a^{\log_a n}\right)^{\frac{1}{\log_a b}} = n^{\frac{1}{\frac{\log_b b}{\log_b a}}}=n^{\log_b a}}$

The recursion tree generated by ${ T(n)=aT(n/b)+f(n) }$1.

Therefore, the total cost is

Let ${ g(n)=\sum_{i=0}^{\log_b n -1} a^i f(n/b^i) }$.

Case #1: Because ${ f(n)=O(n^{\log_b a - \varepsilon}) }$, so there exists ${ c>0,n_0 }$ such that ${ f(n)\leq c\cdot n^{\log_b a - \varepsilon} }$, when ${ n>n_0 }$. Therefore, when ${ n>n_0 }$, we can get

Then we get a geometric series, so

Because ${ b>1,\varepsilon>0 }$, we can get ${ \frac{c}{b^{\varepsilon}-1}>0 }$. Therefore, ${ g(n)=O(n^{\log_b a}) }$, that means

Case #2: Because ${ f(n)=\Theta(n^{\log_b a} (\lg n)^k), k\geq 0 }$, so ${ g(n)=\Theta\left(\sum_{i=0}^{\log_b n -1} a^i \left( \frac{n}{b^i}\right)^{\log_b a} \left( \lg \frac{n}{b^i}\right)^k \right) }$. Let ${ A= \sum_{i=0}^{\log_b n -1} a^i \left( \frac{n}{b^i}\right)^{\log_b a} \left( \lg \frac{n}{b^i}\right)^k}$, we have

Let ${ B = \sum_{i=0}^{\log_b n -1} \left( \lg \frac{n}{b^i}\right)^k}$, we can get

Therefore, ${ g(n)=\Theta(A)=\Theta(n^{\log_b a} B) = \Theta \left( n^{\log_b a}(\lg n)^{k+1} \right) }$.

Another proof with definition of ${ \Theta }$ is here

Because ${ f(n)=\Theta(n^{\log_b a} (\lg n)^k), k\geq 0 }$, so there exists ${ c_1>0,c_2>0,n_0>0 }$ such that ${ c_1\cdot n^{\log_b a} (\lg n)^k \leq f(n) \leq c_2\cdot n^{\log_b a} (\lg n)^k }$, when ${ n>n_0 }$. Therefore, we can getCase #3: Because ${ f(n) }$ is one of the items in ${ g(n) }$, so ${ g(n)=\Omega(f(n)) }$. If we want to prove ${ g(n)=\Theta(f(n)) }$, we just need to prove ${ g(n)=O(f(n)) }$.

In this case, we have ${ af(n/b) \leq (1-\varepsilon’)f(n) }$, that is ${ f(n/b) \leq ((1-\varepsilon’)/a)f(n) }$, so we can get ${ f(n/b^i) \leq ((1-\varepsilon’)/a)^i f(n) }$, that is, ${ a^i f(n/b^i) \leq (1-\varepsilon’)^i f(n) }$. (When ${ n/b^i }$ is sufficient large enough).

Therefore, we can get

Note ${ 1-\varepsilon’ <1}$, so

So, ${ g(n)=O(f(n)) \Rightarrow g(n)=\Theta(f(n)) }$. And, ${ f(n)=\Omega(n^{\log_b a+\varepsilon}) }$, for some ${ \varepsilon >0 }$. Then we can get

-

Cormen, T. H., Leiserson, C. E., Rivest, R. L., & Stein, C. (2022). Introduction to algorithms. MIT press. ↩