This paper proposes a novel data structure, Backpack Quotient Filter (BQF), to index $k$-mer. which support querying with efficient space and negligible false positive rate. Additionally, this blog will introduce Counting Quotient Filter (CQF)1 at first, to lead a better understanding of this work.

Motivation

Problem Definition: if a sequence is present or absent in a database, even better their abundance.

But it’s hard to achieve for a huge database.

$\Rightarrow$ So we have to do pseudo-alignment (only reporting present or not without coordinates on genome). Like, Kallisto.

$\Rightarrow$ “Threshold” pseudo-alignment: at least a fixed fraction $\tau$ of the $k$-mers are found in that genome. Like, Bifrost. In other words, these tools break down queried seqs into $k$-mers; and compare them against datasets (organized as colored Bruijn graph).

But the graph construction is limitation.

$\Rightarrow$ If allow false-positive, some tools use Approximate Membership Queries (AMQ) data structure. Trade off between size and false-positive rate.

Problem Definition: if a $k$-mer is present or absent in a database, even better their abundance.

Data structures covered in these tools.

-

Bloom filter: insert; but high space usage.

-

XOR: static; better space usage.

-

Quotient Filter: dynamicity; Counting Quotient Filter (CQF) can retrieve the absence and abundance. But requiring a lot of space.

Quotient Filter (QF) and Counting QF

Preliminaries

Before diving into the Backpack Quotient Filter (BQF) proposed in this paper, let’s first take a look at Quotient filter (QF) and Count Quotient Filter (CQF) 1. A QF is a table with $2^q$ slots, each of fixed size $r$, where $q,r$ are defined by user. Given a hash function $h$ that hashes each element to a integer of $q+r$ bits, we can split $h(x)$ into two functions, i.e. $h_0(x)$ of $q$ bits, called “quotient” and $h_1(x)$ of $r$ bits, called “remainder”.

- $h_0(x)$, quotient of fingerprint (hash value): it maps to an address in the table, and the corresponding slot called “canonical slot”.

- $h_1(x)$, remainder of fingerprint: we try to store $h_1(x)$ in some slot of table.

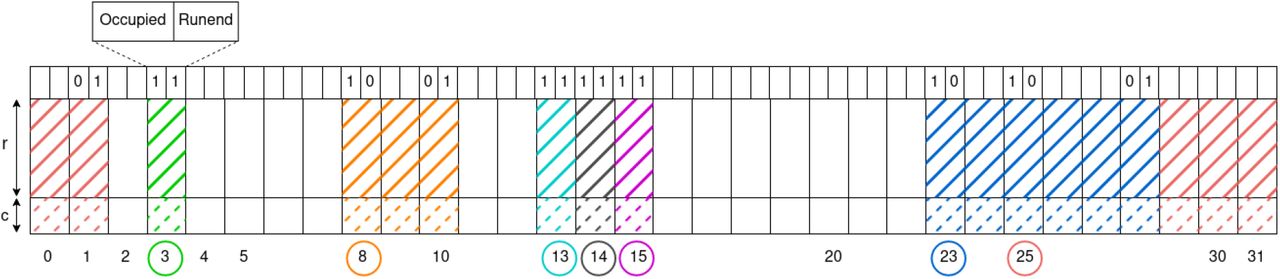

Fig.1 Quotient Filter2.

Basically, the idea is if we have an element, say a $k$-mer $x$, we calculate $h_0(x)$, i.e. the canonical slot and try to store $h_1(x)$. If the slot is empty, we are fine. But in most cases, it’s occupied. How does this happen?

- Hard collision: two distinct elements have the same hash value. We avoid this by using a prefect hash function.

- Soft collision: It is inherent to quotient filters. A soft collision occurs when two distinct elements x and y have different hashes but the same quotient: $h_0(x) = h_0(y)$.

Rank-Select Scheme

To address this collision, we have to shift the reminder into next slots. In other words, elements with same quotient are stored consecutively in the table, which form a “run” (shown in a same color in above figure). Inside a run, the QF guarantee the remainders are stored in ascending order.

Metadata bits

Thus, above operations lead to another problem, that is even the first element of a run $x_\text{first}$ maybe not locate in $h_0(x_\text{first})$, because upstream runs could occupy this canonical slot. To keep track of the shifting distance, we assign two bits metadata.

- The occupied bit determines whether a slot is a canonical slot for some inserted element, whose remainder could be shifted and located elsewhere.

- The runend bit indicates whether a slot stores a remainder that is at the end of a run. In this case, it is set to 1. Otherwise, it is set to zero, and in this situation, the next slot is either empty or is the first one of a different run.

Rank, Select and Offset

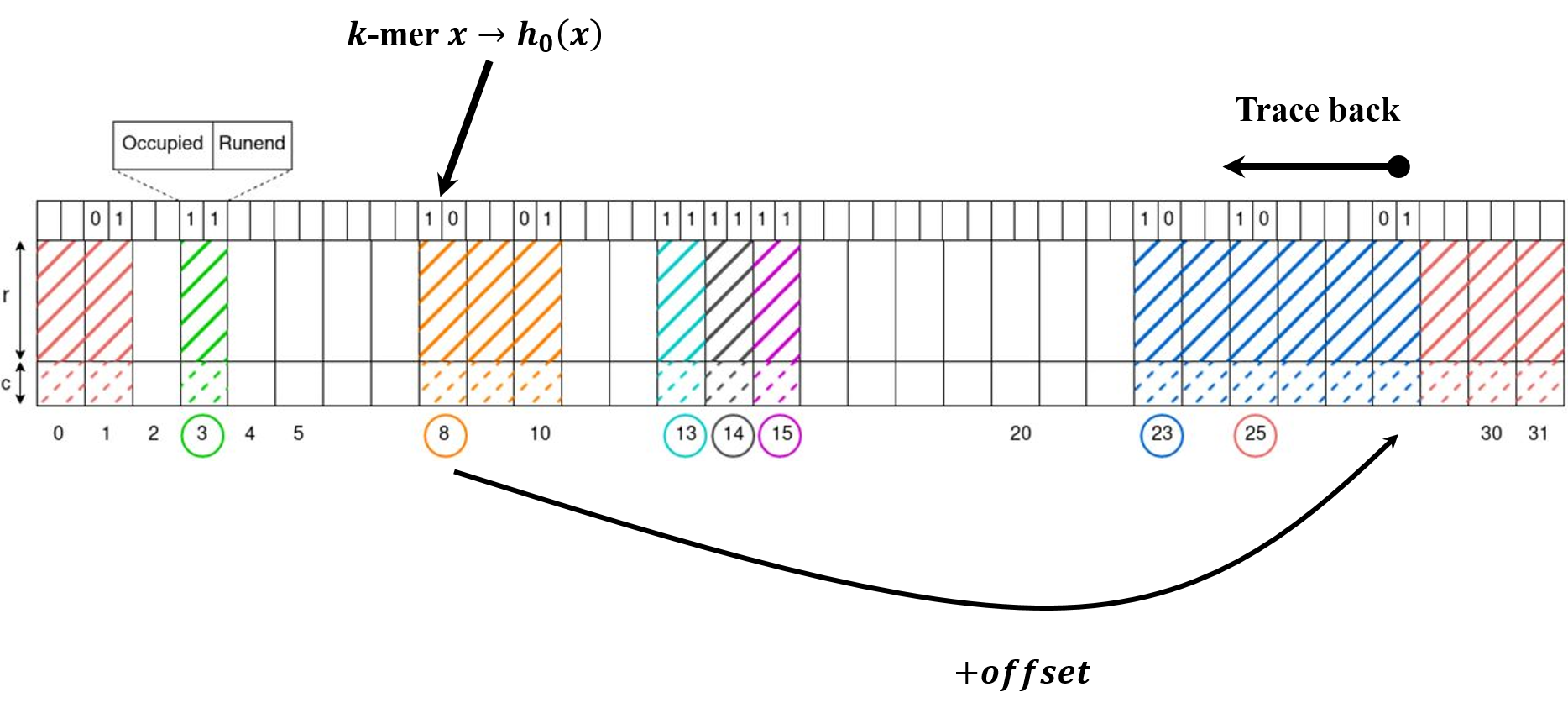

Given a $k$-mer $x$, we first calculate the quotient $i=h_0(x)$, and then we aim to find the end of this run with quotient $i$. Because no matter we do insertion or query, we need to locate at the end of run, and compare the remainder one by one reversely (see Fig. 2).

The above two metadata bits of all the slots form two binary vector called occupieds and runends. We define following two operations.

- $\textbf{Rank}(occupieds,i)$: counting the number $d$ of runs that present before $i$, i.e. counting the number of $1$ in vector occupieds before $i$.

- $\textbf{Select}(runends, d)$: find the position of $d^\text{th}$ $1$ in vector runends.

Thus, we can get the end of runs with quotient $i$, $\textbf{Select}(runends, \textbf{Rank}(occupied,i))$. To do it efficiently, we can define this shifting distance as Offset and store the information. To pursue a better trade-off between space and speed, QF are divided into blocks of 64 slots. QF uses 64 bits integer to store the offset of the first slot in block as checkpoint. (The metadata will be $3$ bits per slot. In origin CQF paper, they set 8 bits integer for Offset.)

Fig. 2 rank and select.

Given a slot $j$, and position $i$ as the first slot of corresponding block, we calculate the position of end of the run as

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} d &= \textbf{Rank}(occupies[i+1:j],j-i+1) \\ t &= \textbf{Select}(runends[i+Offset(i)+1,2^q-1],d) \\ \text{Position}_\text{runend}(j) &= i + Offset(i) + t \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]The above calculation can be virtualized as below Fig. 3

Fig. 3 Procedure for computing offset $O_j$ given $O_i$1.

Lookup and Insertion

If we want look up a query element if it’s in the QF, we first call above rank-select scheme to get the position of the end of the run. Then, trace back to look at if we have same reminder in the table (shown in Fig. 2). If $occupieds[h_0(x)]=0$, we can directly return false.

For insertion, basically, we use the same logic to do. But, we may need to jump several times to find an empty slot and shift remainders to make a room for new one.

The details of above two algorithms can be found in CQF paper1. The above data structure is called rank-and-select-based quotient filter (RSQF). We should noticed that RSQF supports enumerating all the hash values in the filter, and hence can be resized by building a new table with $2^{q+\delta}$ slots, each with a remainder of size $r-\delta$ bits, and then inserting all the hashes from the old filter into the new one.

Counting Quotient Filter

If we hope to support the abundance query for $k$-mers, we modify above QF to Counting Quotient Filter (CQF). In general, CQF can store abundance information or remainder for each slot. The encoding rules are shown in below table.

Basically, we use use two remainders as boundary and encode count use middle slots. We should notice that, we cannot use $0$ and remainder $x$ in each slot to eliminate ambiguity. In other word, we use $1,2,\cdots,x-1,x+1,\cdots,2^r-1$ to encode base $2^r-2$ for each middle slot and pad $0$ before significant bit $c_{\ell-1}$ (that is because the logic of CQF checking abundance information is judge if the remainder is increasing, otherwise we know the following slot will be encoding of count.)

Here are three examples to help understanding.

- Remainder $0$ has 5 copies. Then, we encode $5-3=2$ as abundance information, i.e. $\underline{0,2,0}$.

- Remainder $9$ has 8 copies. Then, we encode $9-2=7$ as abundance information, i.e. $\underline{9,7,9}$.

- Remainder $3$ has 7 copies. Then, we encode $7-2=5$ as abundance information, but $5>3$, so in fact here we use $6$ to encode $5$, and we need to pad $0$ i.e. $\underline{3,0,6,3}$.

Method of BQF

BQF uses a xorshift hash function, producing numbers between $0$ and $2^{2k}$ for every $k$-mer, which is a Perfect Hash Function and reversible.

Storing abundance

Instead of using above complicated encoding in CQF. BQF just add extra $c$ bits for each slot to store abundance, which adding $c\times 2^q$ bits.

Reducing the space usage

If we use PHF to store $k$-mers, the QF can have exact quires. To make better space usage, BQF will sacrifice performance. Specifically, we store all the $s$-mer rather than $k$-mer, and report present when all the $s$-mers of a given $k$-mer are exists in filter.

Correspondingly, we store the abundance of $s$-mer in $c$ bits mentioned before. We know the abundance of a $k$-mer is at most the minimum abundance of the $s$-mers. BQF will report this value as the abundance of the query $k$-mer.

By doing so, the size of hash integer is $2s$ instead of $2k$. If we keep $q$ as same, then each slot will decrease $2(k-s)$ bits. This modification will lost the feature of enumerating $k$-mers, but still support resizing filter, comparing to CQF mentioned in last chapter. The influence of decreasing $s$ are

- Increase False positive rate

- Increase the number of indexed element. We will add $k-s$ additional elements per sequence.

- Decreasing $2^q \times 2(k-s)$ bits.

Results

Compared Performance

Notice:

- pre-processing time: the time used to obtain the correct input file from the raw compressed fastq file.

- $k=32,s=19,c=5$ set for Counting Bloom Filter, CQF, BQF.

- Positive queries in a dataset $D$ are $k$-mers from $D$ itself. Negative queries are $k$-mers from randomly generated sequences.

- CBF size was set to be the same as BQF’s,

Impact of $s$

Fig. 4 Impact of $s$ in an Illumina sequencing dataset (seawater34M)1.

To guarantee acceptable false positive rate, we need $s \geq 17$. We will find the number of $s$-mer is decrease. In theoretical, we know the conflict effect of decreasing $s$ mentioned before. But we observe the decreasing of “bits per element” empirically. The red curve and orange curve correspond to half-fill BQF and 95%-full BQF, respectively.

Effect of the number of elements

Fig. 5: Effect of the number of elements on the size and space efficiency1.

We should noticed that the peaks in Fig. 5(B) get lower while the data structure size doubles. Because the slots are one bit shorter after each resize.

Thoughts

Main contribution is use $s$-mer rather than $k$-mer. It’s a trade-off between space and false positive rate and also sacrifice the accuracy of abundance.

What could be better?

- Choosing $c$ bits to encoding abundance, if we could employ the properties to have better space usage. Because, the remainder in a run is increase, if we can have better encoding?

- If we have some “locality-preserving” hash function (not MPHF), the neighbors of $k$-mer will store together, if we can compress the abundance, because neighbors could have similar count.

-

Prashant Pandey, Michael A. Bender, Rob Johnson, and Rob Patro. A General-Purpose Counting Filter: Making Every Bit Count. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Conference on Management of Data, SIGMOD ’17, pages 775–787, New York, NY, USA, 2017. Association for Computing Machinery.. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

The Backpack Quotient Filter: a dynamic and space-efficient data structure for querying k-mers with abundance ↩